How to Digest Quantum Computing

David Crawford / December 15, 2025

"It's too complicated," is what most people say about quantum computing. But day after day, the research continues, and someone is figuring things out. Companies are investing billions, and governments are pouring in resources. The same thing happened with Machine Learning. During its research stages, most people who looked at it thought it was too complicated. But now it's common place, but not a lot of people know how it's made.

It's the same for quantum computing, and I've found that there's actually a lot of gate-keeping going on, where everyone "in the know" tells you that you need to study for years in math and physics and get a PhD before you can understand anything about it. This is simply not true.

This past month, I wanted to understand quantum computing better, build something practical, and then share the process.

Something Practical

Imagine the entire United States' social security numbers being stored in a single lookup database. Hundreds of millions of unique entries, all unsorted, with no indexing, hashing, or structure. Now, you need to make a query to find one. How long will it take?

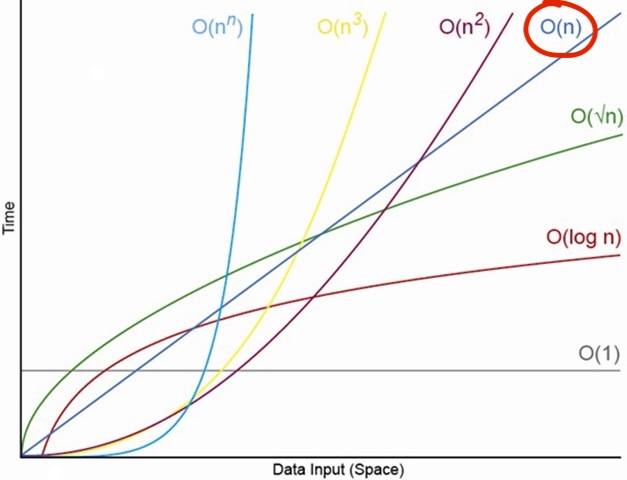

In classical computing, we use O(n) notation to describe the time complexity of searching through this database. In the worst case, you might have to look through every single entry, which means the time taken grows linearly with the number of entries.

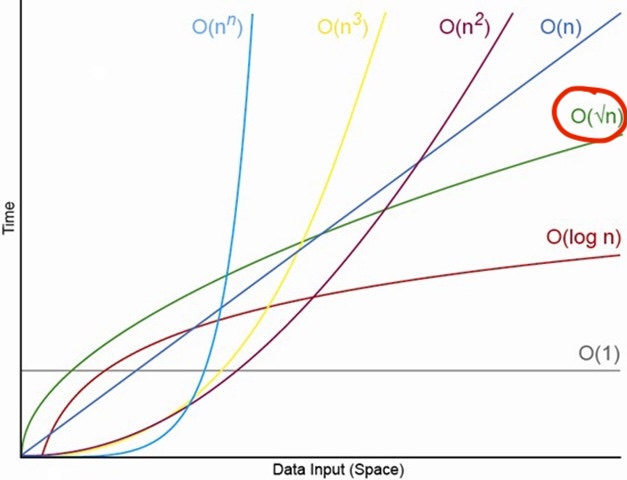

How can we possibly make this faster? With quantum computing, we can use Grover's algorithm, which allows us to search through an unsorted database in O(√n) time, or a quadratic speedup for unstructured searching. This means that instead of checking each entry one by one, we can cut the work down to a tiny fraction of the effort, letting the algorithm “home in” on the right answer with far fewer steps than any classical approach could ever manage.

Worth mentioning: Grover's algorithm doesn’t check entries faster. It amplifies the probability of measuring the correct answer via repeated quantum rotations.

O(√n) complexity also means that the larger the database, the faster the speedup.

So what are we waiting for? Why isn't everyone using quantum computing for search problems? If you have to tackle my SSN example and not what it represents first, know that nearly all databases in the real world can utilize indexing, hashing, B-trees, etc. in order to acheive O(log n) or even O(1) time complexity for lookups. These classical data structures and algorithms are incredibly efficient for structured data, making them the preferred choice in most applications.

To understand why Grover's algorithm, and thus, quantum algorithms, aren't being used in the field, we need to walk through the fundamentals, and the answer will become clear.

The Fundamentals

From Microsoft's Quantum Katas curriculum

I want to preface this by saying that I got a D- in Calc 1 in college, and it's possible that I gave my grandpa, who has a Masters in Computer Science, every gray hair he has today from when he would try tutoring me. So if I could learn some basics about quantum computing, you can too. My journey started with Microsoft, which has a Quantum Katas series. If you have any desire to solve some math problems by hand, I highly recommend their series. I finished the whole thing in a month, and felt like I could understand what's generally going on with basic quantum algorithms and running code. The titles make it look super complicated, but the byte size material helped a lot.

My notes from the curriculum

My key takeaways from the material:

- A bit is either a 0 or 1

- In the quantum computing world, we use qubits, which can be both 0 and 1 at the same time (superposition)

- Qubits can be entangled, meaning the state of one qubit can depend on the state of another, no matter the distance between them

- When we look at the value of a qubit in order to practically use it (measurement), it collapses a qubit's superposition into a definite state (0 or 1)

- Quantum gates manipulate qubits, changing their states and creating entanglement

- Quantum algorithms leverage superposition and entanglement to solve problems more efficiently than classical algorithms

- Real quantum computers have limited qubit counts and high error rates, making practical applications challenging, or impossible

Okay, great? Some of this could look like nonsense, so here's the two that were the most important for me, and what they mean:

Measuring a qubits collapses its superposition

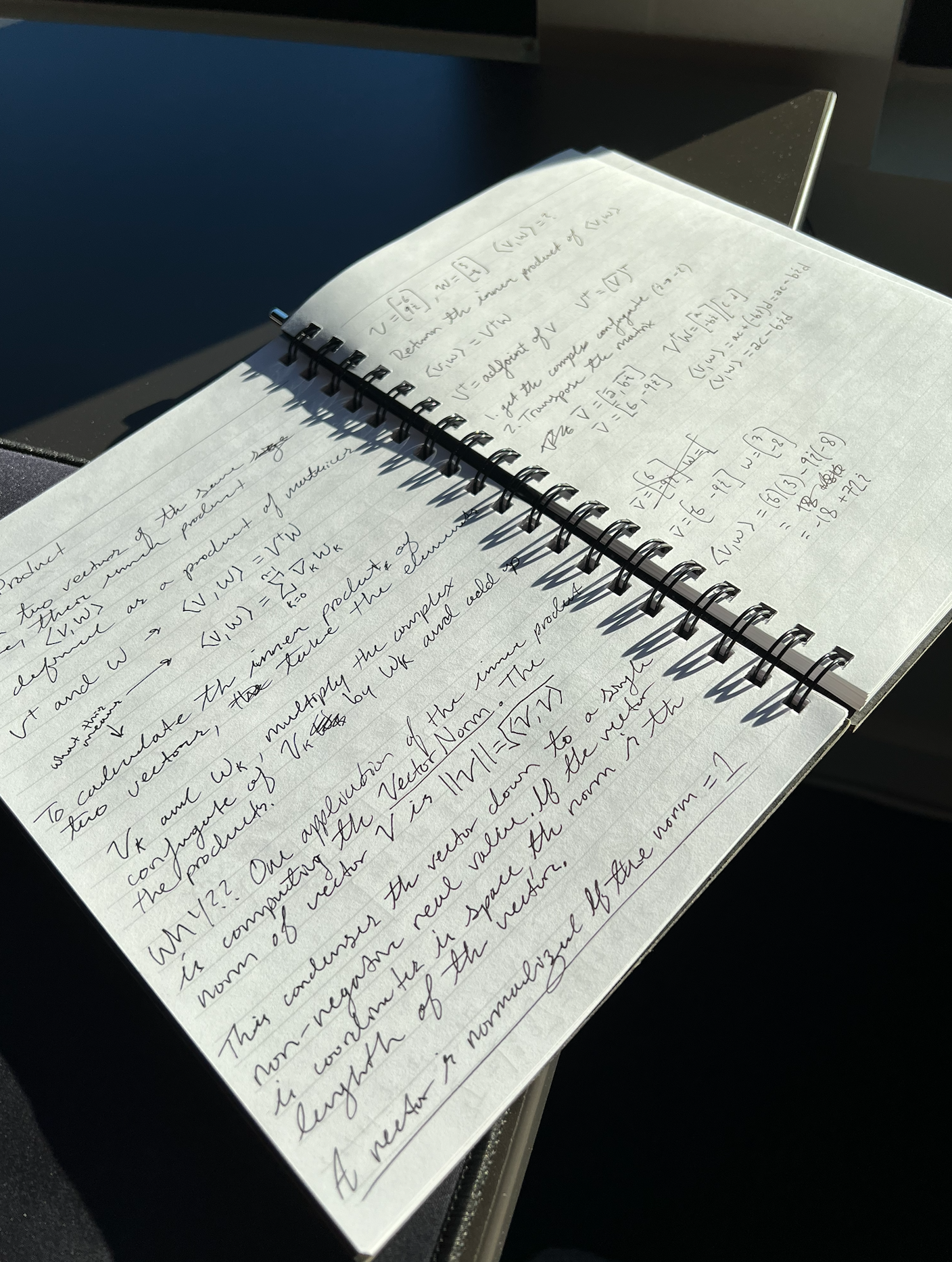

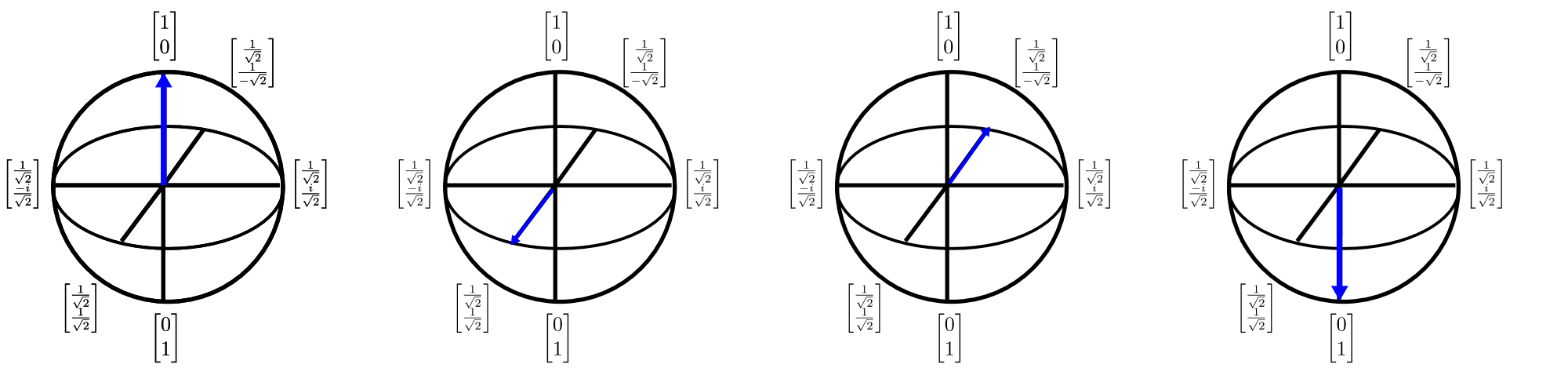

A Bloch Sphere representation of a qubit

In the above diagram, we see a 3D (Block Sphere) representation of a qubit. The north pole represents the state |0⟩, and the south pole represents the state |1⟩. Any point on the surface of the sphere represents a superposition of these two states. When we measure the qubit, it collapses to either |0⟩ or |1⟩ based on its position on the sphere.

This is useful because superposition allows a quantum computer to perform operations on all possible states simultaneously. However, the final measurement only gives on output, so our algorithm must be designed so that:

- Constructive inference boosts the correct answer's probability

- Destructive interference reduces the probabilities of incorrect answers

So with Grover's algorithm, we simultaneously explore all entries in the database, and amplify the probability of the correct entry being measured when we finally collapse the qubits.

Real quantum computers have high error rates

This is the biggest problem today, and I'll demonstrate this with real code we can run on an actual quantum computer. Quantum computers right now have incredibly high error rates because qubits are fragile and the environment they exist in is constantly trying to destroy any real quantum information.

Stray heat, electromagnetic fields, cosmic rays, vibrations, imperfection in materials, microwave pulses meant for one qubit but leak to a neighbor,and more, all contribute to qubit decoherence, where the qubits lose their quantum properties and behave more like classical bits. This means that the longer a quantum computation runs, the more likely it is to produce incorrect results due to these errors.

With today's technology, to quote John Sheridan from Babylon 5:

The more qubits a quantum computer has, the more the noise scales and the machine gets harder to stabilize.

But what about the day when error rates are low enough, and we have enough qubits to solve classical problems faster with quantum algorithms? How can we prepare?

I think the best way to start is with my SSN search example, by implementing Grover's algorithm on a small scale, and then running it on a real quantum computer to see how it performs.

Implementing Grover's Algorithm

- Start by creating a free trial account with IBM's Quantum platform here. You'll be allotted a generous amount of free and real quantum compute time each month.

- Clone my Grover's algorithm repo from GitHub here -

git clone git@github.com:DaveAldon/Quantum-Experiments.git - Create an

.envfile in the root of the project with your IBM Quantum API token, and the instance ID:

IBM_QUANTUM_TOKEN=

IBM_QUANTUM_INSTANCE=

- Run

pip install -r requirements.txtto install the dependencies, thenpython fast_search.pyto execute the Grover's algorithm implementation.

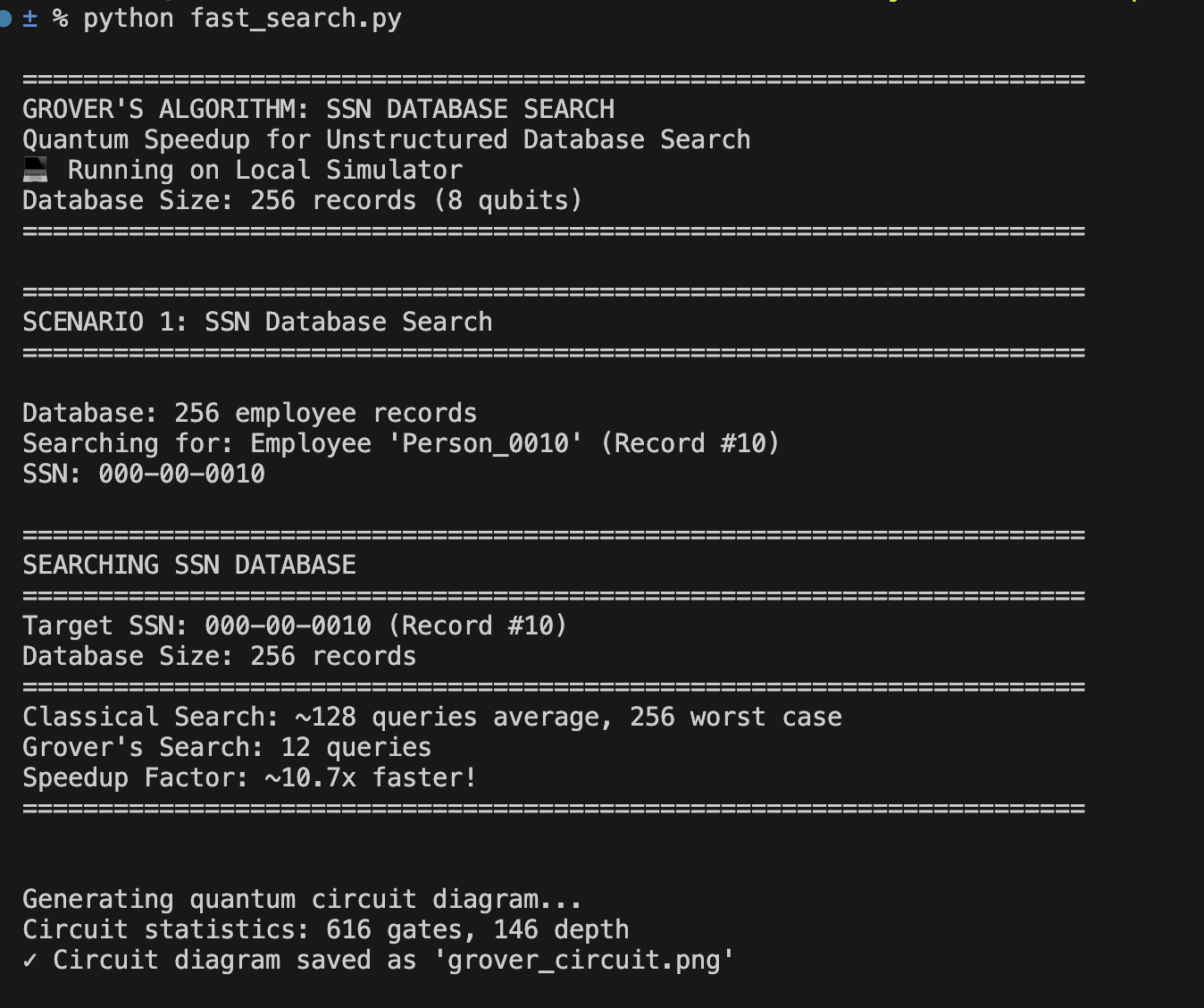

Once it's done, you should see some output like below:

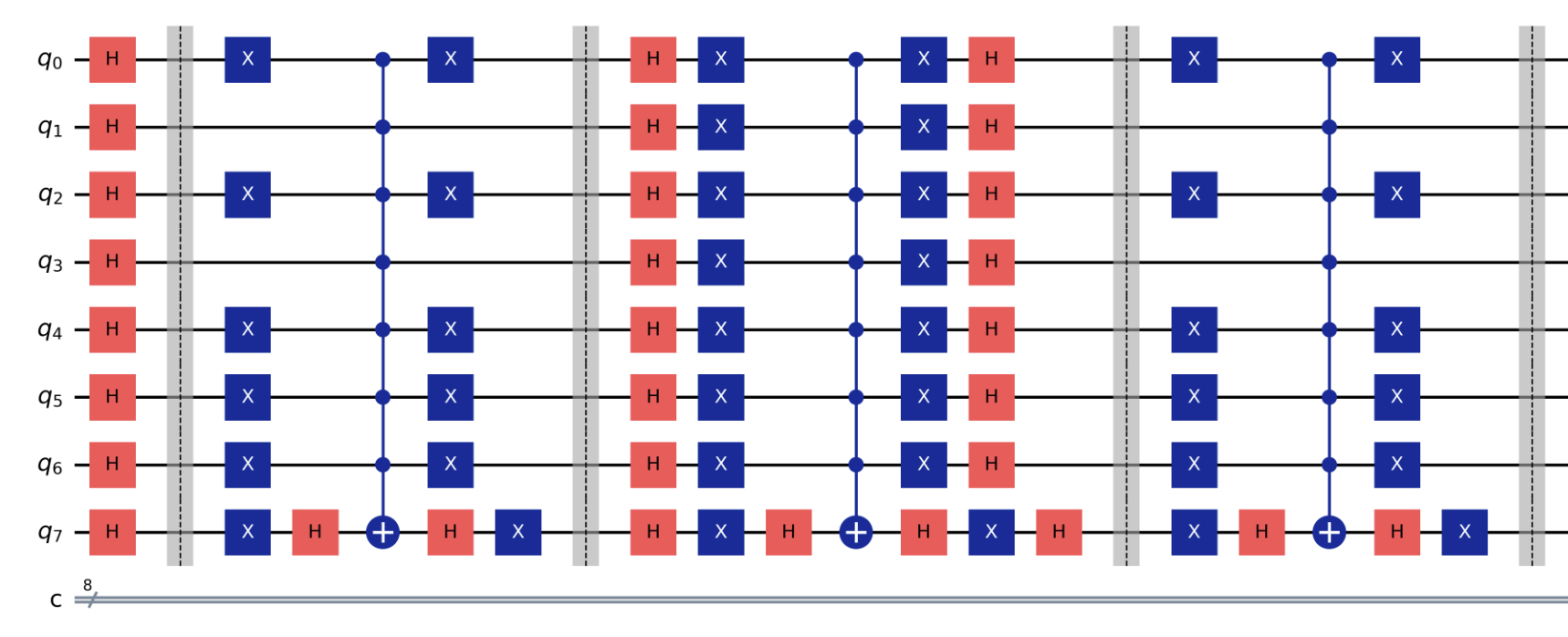

It also outputs a circuit diagram which can be very helpful for understanding how the algorithm is structured (this is a small portion of the diagram):

How to read these diagrams (which will make you look really smart when reading Quantum research papers):

-

The red H gates (Hadamard, the most fundamental quantum operation) create an equal superposition of all possible states -

2^8 = 256states for 8 qubits- Before the H gates, the register is

|00000000⟩ - After the H gates, the register is

This means that the quantum computer is actually trying all 256 possible entries at the same time!

- Before the H gates, the register is

-

The blue boxes represent the Grover Oracle, which marks the correct answer by flipping its phase

- If the targeted SSN value in binary is

10101010, the oracle flips the amplitude of that state and leaves everything else alone - This can also be represented like an if statement:

if state == target: multiply amplitude by -1 - If the targeted SSN value in binary is

-

The ⊕ symbols are where the amplitude is flipped if all the qubits match the target pattern

Each repetition, as the diagram continues, sharpens the probability of measuring the correct answer.

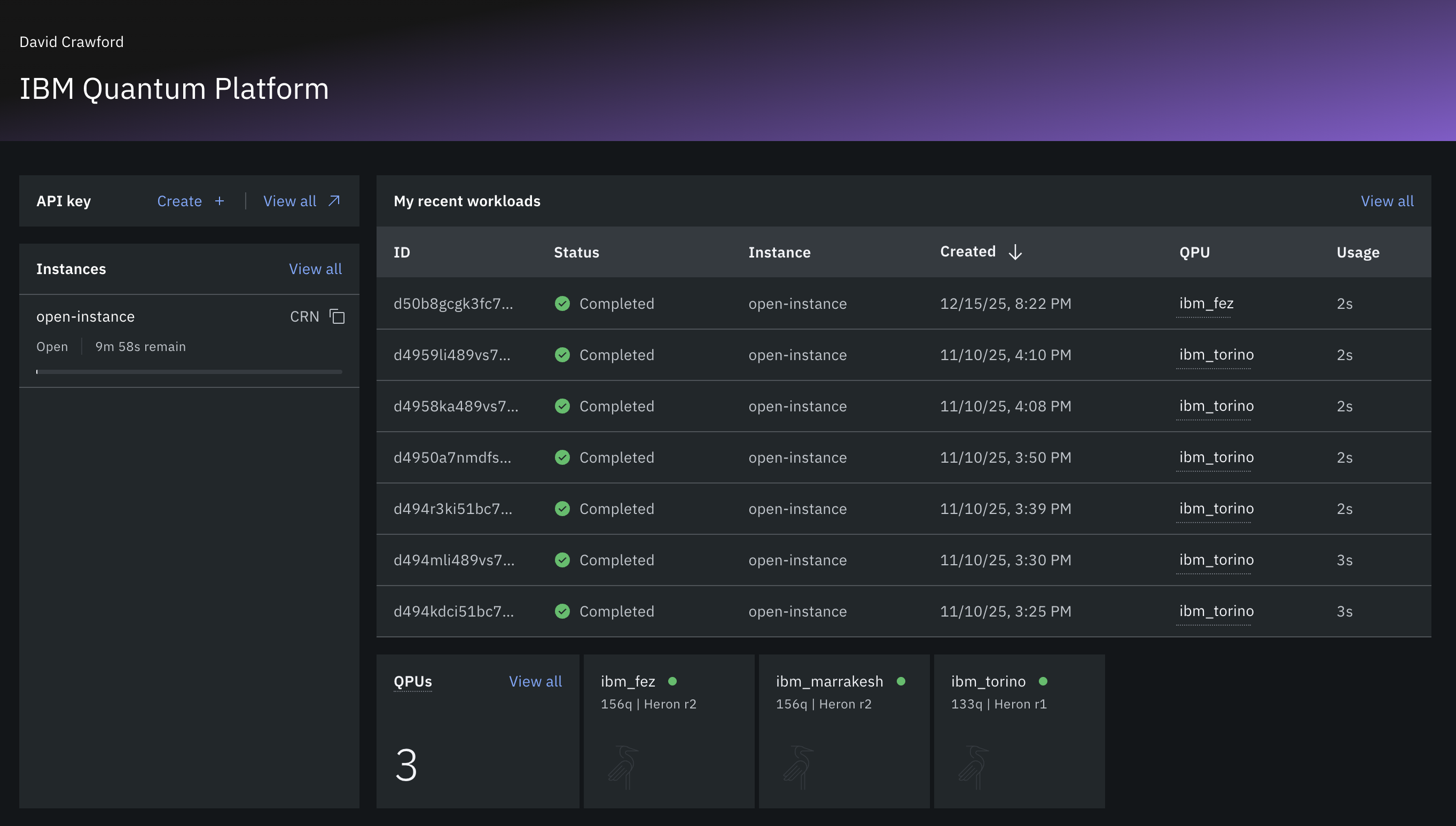

Sending to the IBM Queue

What I didn't tell you is that the code you just ran executed simply a simulation of quantum computing on your local machine. This is good practice for testing so that you don't waste time and API credits.

If everything ran correctly, send it to the IBM queue by running this command:

python fast_search.py --use-ibm --qubits 4

IBM Quantum dashboard showing job status

Why only 4 qubits? Because real quantum computers today have high error rates, and the more qubits you use, the more noise you introduce. By using 4 qubits, we're greatly reducing the chance of errors, while still demonstrating Grover's algorithm in action.

When I originally worked on this code, I tried as many qubits as possible, thinking that this would speed things up. But the results were complete garbage and it couldn't handle the noise, so the probabilities were all over the place and it performed worse than classical searches! So we have to reduce the qubits here to get a reliable result. Even though this isn't the "perfect" example, it works.

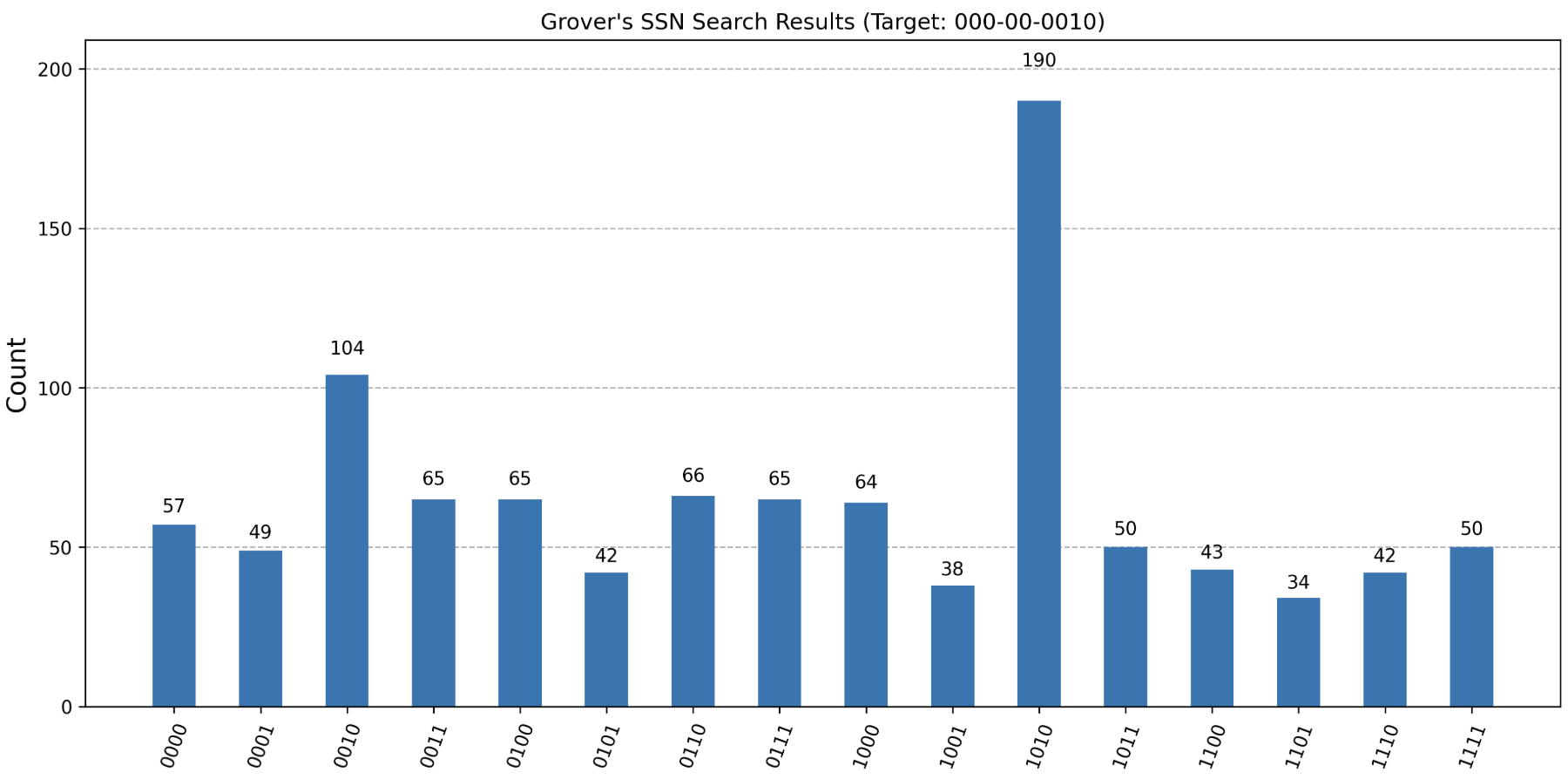

After the code runs, you can verify how it performed by checking out the histogram it produces:

You can see that the highest bar corresponds to the correct answer, which is 1010 in binary, or 10 in decimal. This means that even with the noise and errors present in today's quantum computers, Grover's algorithm was able to amplify the probability of measuring the correct answer.

Is it really that easy?

Writing quantum code is actually pretty straightforward once you understand the fundamentals. Libraries like Qiskit (used in this example) let us use Python which is great and has less of a learning curve. Q# from Microsoft is a nice dedicated language as well, but of course requires more setup to run, and I'm lazy.

Let's look at the key section of the Grover function I wrote, with comments to explain each step, which reflect what we've been discussing so far:

# Creates a new quantum circuit with however many qubits we want

qc = QuantumCircuit(n_qubits, n_qubits)

# Applies the Hadamard gate to the qubits, putting them into superposition.

qc.h(range(n_qubits))

# Checkpoints so that the circuit optimizer, when the code is compiled, doesn't rearrange gates in ways that break the algorithm's logic

qc.barrier()

# Creates the oracle (self explanatory, right?), or subroutine, that marks the target we're looking for and applies a phase flip (multiplying the value by -1). This is the step from the circuit diagram with the blue boxes

oracle = create_oracle(n_qubits, target_state)

# The diffuser amplifies the probability of measuring the correct answer

diffuser = create_diffuser(n_qubits)

# Repeat the oracle and diffuser for the optimal number of iterations.

# optimal_iterations = The mathematically proven optimal number of times you need to repeat the oracle->diffuser cycle to find the target with near certainty, or O(√N) times.

for i in range(optimal_iterations):

qc.compose(oracle, inplace=True)

qc.barrier()

qc.compose(diffuser, inplace=True)

qc.barrier()

# Measure all qubits to get the result. This is the final step in the circuit diagram with the measurement boxes.

# The qubits are collapsed to classical bits here.

qc.measure(range(n_qubits), range(n_qubits))

if draw_circuit:

print("\nQuantum Circuit:")

print(qc.draw(fold=-1))

print()

return qc, optimal_iterations

Final Thoughts

All this quantum nonsense can seem overwhelming at first, but I firmly believe it's worth understanding the fundamentals, because eventually quantum computing will have less errors, and be more accessible. By starting with small experiments like Grover's algorithm on real quantum hardware, we can prepare ourselves for the future where quantum computing plays a significant role in solving complex problems.

And which complex problems will those be? At the moment, you'll end up finding that theoretical quantum applications are only best at solving...quantum problems, and possibly factoring obscenely large numbers. A lot of the cryptography, optimizations (like Grover), and machine learning applications of quantum computing are...incredibly niche and not likely to be useful (even though I showed how to do it here, but I still think they're helpful and approachable). They tend to be more popular for marketing hype. You cannot really "speed up" classical computing problems by throwing quantum at it. Quantum problems are solvable with quantum computing, and classical problems are solvable with classical computing. The two don't really mix well.

I highly recommend this video if you're interested in a more realistic perspective on quantum computing, vs. the marketing hype: